CENTRAL BANKERS IN A BOX

February 7, 2015

The environment in the

global financial markets continues to grow more interesting as it deals

with extreme monetary policies, deflationary pressures in the real

economy and the competition for global trade in the midst of overall

muted growth. This month

let’s take a look at the increasing challenges the Federal Reserve is

facing and a few new bizarre developments in the financial markets.

First, let’s see how

this brilliant central bank of ours continues to box themselves into a

more challenging position.

Over the past five years they have kept interest rates at zero and have

printed trillions of dollars and the rest of the world central banks

have followed their strategy at an increasing pace.

This month I won’t go into all the reasons why they never should

have printed all this money or cut rates to zero, much less why they

should have raised rates earlier.

So, the unemployment

rate stands at 5.7% and job growth from the government numbers was

pretty strong in January.

Wage growth was much better as well.

The Fed is starting to feel pressure from some of the economic

numbers in the U.S. to move rates higher since most would think that

zero interest rates is more indicative of an environment like the

financial panic in 2008. As

a result, many are forecasting that the Fed will begin to raise rates

starting in June. Since the

Fed tends to rely more on coincident economic data points like the

monthly payroll numbers rather than leading indicators, more Fed members

have recently confirmed that a rate hike is likely to come mid-year.

It is our central bank

that started the competitive devaluation game that is being played

around the world. Since

global growth is slow and may be slowing, countries are increasingly

trying to devalue their currency to make their goods cheaper and capture

more global trade. The

European Central Bank recently announced that they are going to print a

trillion dollars over the next year, smaller developing countries are

cutting rates and it even looks like China may start targeting their

currency more aggressively as they are struggling with slowing growth.

While many countries

around the world are following our lead and moving more forcefully

toward devaluing their currency, our Fed is now facing pressure to raise

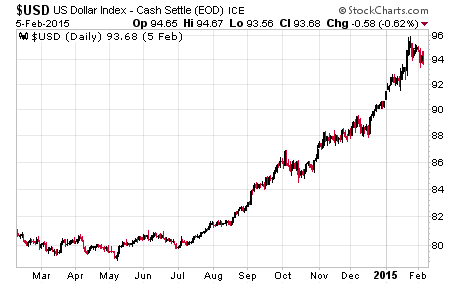

rates and this has been reflected in the rapid rise in the U.S. dollar.

Here is a chart to illustrate the rise.

Just in the last seven

months, our currency has risen by over 20%.

Now, what do you think we are likely to hear from our companies

in the U.S. who are competing for global trade?

This earnings season we have heard more and more companies

talking about the challenges they are facing from the rising dollar.

We are likely to start hearing more opposition to the Fed’s plan

to begin raising rates from more of our corporate leaders.

CENTRAL BANKERS IN THE ROACH

MOTEL…

Just in the last week,

two high profile leaders in the corporate world have voiced their

opinions on this; Jack Welch, former CEO of GE, and Warren Buffett.

Welch was interviewed this week on CNBC and said, “The Federal

Reserve would be crazy to increase interest rates in the near future.

It would be insane.

Your exports would fall off the table even more.”

Then, Warren Buffett

chimed in as reported in an article by CNBC.

“With the rise of new international conflicts and foreign

countries diluting their currencies, Warren Buffett said it would not be

feasible for the Federal Reserve to increase rates.

‘If Europe's got them at zero, and you get higher rates in the

United States, that would exacerbate a problem with the stronger dollar

and funds flow,’ the Oracle of Omaha said on Wednesday.”

This week the U.S.

trade balance for December was released.

Our trade deficit was much higher than expectations and soared

17.1%. This will cause

notable downward revisions to 4th quarter GDP.

Corporate America will increasingly apply pressure to the Federal

Reserve not to raise rates due to the currency impact.

Once you start down this game of competitive devaluations, it

becomes more and more challenging to exit the game.

It is the roach motel of monetary policy.

So, on the one hand,

you have Welch and Buffett leading the charge from corporations warning

the Fed they had better not raise rates due to the currency issues, and

then on the other hand, you have economists jumping up and down over the

“wonderful” January employment report and claiming that the Fed better

start now in raising rates or they are going to get behind the curve.

Let’s dive a little deeper to see if the economists have much of

a case relating to the job gains and wage increases in January.

WHAT A FANTASTIC JOB MARKET…

First, let’s take a

look at an article by Jim Clifton, CEO of Gallup.

“Here's something that many Americans -- including some of the

smartest and most educated among us -- don't know: The official

unemployment rate, as reported by the U.S. Department of Labor, is

extremely misleading. Right

now, we're hearing much celebrating from the media, the White House and

Wall Street about how unemployment is ‘down’ to 5.6%.

The cheerleading for this number is deafening.

The media loves a comeback story, the White House wants to score

political points and Wall Street would like you to stay in the market.”

“None of them will tell

you this: If you, a family member or anyone is unemployed and has

subsequently given up on finding a job -- if you are so hopelessly out

of work that you've stopped looking over the past four weeks -- the

Department of Labor doesn't count you as unemployed.

That's right.

While you are as unemployed as

one can possibly be, and tragically may never find work again, you are

not counted in the figure we see relentlessly in the news -- currently

5.6%. Right now, as many as 30

million Americans are either out of work or severely underemployed.

Trust me, the vast majority of

them aren't throwing parties to toast ‘falling’ unemployment.”

“There's another reason

why the official rate is misleading. Say

you're an out-of-work engineer or healthcare worker or construction

worker or retail manager: If you perform a minimum of one hour of work

in a week and are paid at least $20 -- maybe someone pays you to mow

their lawn -- you're not officially counted as unemployed in the

much-reported 5.6%. Few

Americans know this.”

“Yet another figure of

importance that doesn't get much press: those working part time but

wanting full-time work. If you

have a degree in chemistry or math and are working 10 hours part time

because it is all you can find -- in other words, you are severely

underemployed -- the government doesn't count you in the 5.6%.

Few Americans know this.”

In a follow up

interview, Clifton said, “The number of full-time jobs, and that’s what

everybody wants, as a percent of the population, is the lowest it’s ever

been…The other thing that is very misleading about that number is the

more people that drop out, the better the number gets.

In the recession we lost 13 million jobs.

Only 3 million have come back.

You don’t see that in the number.”

MINIMUM WAGE AND UNEMPLOYMENT

BENEFITS SKEW DATA…

So, Clifton addresses

the quality of the government jobs data.

Now, let’s see what ECRI [Economic Cycle Research Institute]

noted about the actual job and wage gains.

“Certainly, yoy [year-over-year] growth in the number of people

with a single job has been trending up over the past year or so.

But the real surge was in yoy

job growth for multiple jobholders, which remains near October’s 18-year

high, accounting for a disproportionate share of the past year’s job

gains, following the termination of extended unemployment benefits at

the end of 2013.”

ECRI highlights that at

the end of 2013, extended unemployment benefits were terminated.

“Surprisingly”, job gains as noted by the government picked up.

As people are cut off from payments from the government, they

have more incentive to find something out there to earn some money.

Remember that if you work at least one hour a week and get paid

at least $20 you are not counted as unemployed, since you found a “job”.

Also, ECRI notes that much of the jobs gains came from multiple

job holders. This indicates

that the type of jobs that are being created are part-time or low

quality since many are having to find multiple sources of work to

support themselves.

If we look back at

December, wage growth was negative.

Subsequently, we saw wage gains in January which the economists

were excited about since it gave them some hope regarding the

deflationary pressures.

ECRI sheds some light over the wage gains this past month.

They noted that the boost in January coincided with a rise in the

minimum wage in many states.

That indicates that the wage gains did not come from market

forces and any gains in the near-term may be dependent on other states

joining the minimum wage increases.

That is not the type of wage gains that suggest healthy economic

growth or relief from deflationary pressures.

A DEEPER ISSUE…

Next, let’s take a look

at what may be more of a structural challenge for the economy as we move

forward. An article by

Steve Goldstein, at MarketWatch, noted that the Labor Department tracked

productivity growth in the economy at -1.8% for the 4th

quarter of last year and that productivity grew only 0.8% for the year.

Also, since the last recession, productivity has not increased by

more than 1% in any year. This is partly a reflection of the weak

capital investment by corporations.

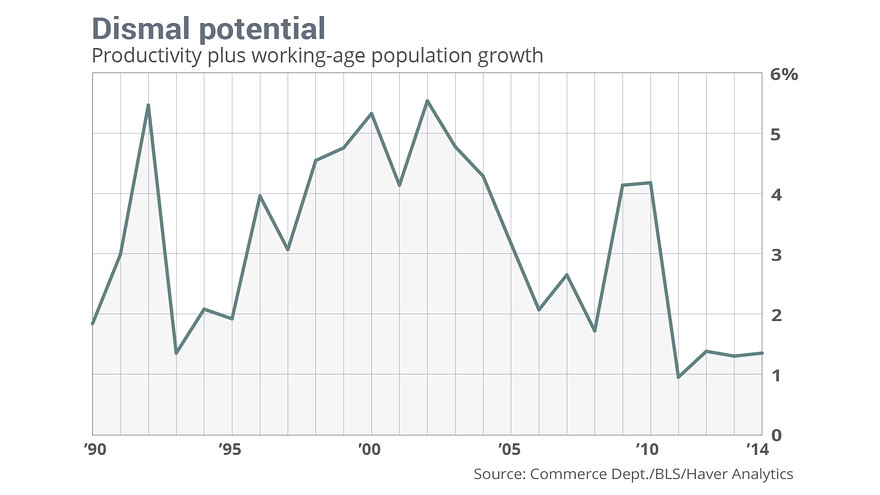

Goldstein notes that a

quick estimate of growth potential for the U.S. economy is the sum of

productivity growth plus the growth in the working-age population.

The working age population is expected to decline from 0.5%

currently to 0.2% in 10-years’ time.

In 2000, the last year that the economy grew over 4%, the

working-age population grew 2.1%.

The muted productivity and working-age population growth is shown

in the chart below.

The anemic economic

growth that we have seen since 2008 is likely to continue.

This is further evidence of how Fed policy has been ineffective

in helping the real economy.

LEADING INDICATORS ARE

SLOWING…

It is also worth

highlighting ECRI’s leading indicator for economic growth in the U.S.

Their weekly leading

indicator suggests that growth may actually slow in the U.S. in the

coming months and recouple with the weakness that is going on in most

areas of the world economy.

All of this likely

suggests that the Fed will not end up raising rates in June, or if they

do, they will find that the market starts to price in a policy mistake

due to the realization of a slowing economy and increasing pressure on

trade from the rising dollar.

THE BIZZARRO WORLD…

Before I close, let’s

highlight a few of the growing bizarre developments in the world of

finance around the globe.

-

German 10-year bund yields have now dropped

below 10-year Japanese Government bond yields – wasn’t the worst of

deflationary pressures in Japan?

-

Following 3 consecutive rate cuts by the Danish

Central bank, BBC News reported that a local bank offered a mortgage

with a negative interest rate!

In effect, with negative interest rates, you could have savers

pay the bank to hold their money and the bank pays the debtor to take

out a loan!

-

Noted by CNN Money, chocolate is the new

gold…the yield on Nestlé’s corporate debt went negative this week.

That means that investors are willing to pay Nestle for the right

to park their money in the safety of the Swiss chocolate company!

The Euro denominated bonds of Bank of America, GE and McDonald’s

are all near zero.

-

In the same article by CNN Money, it highlights

that the central bank moves have knocked the yields on various

government bonds into negative territory including Belgium,

Denmark, France, Germany, Japan and the Netherlands.

Investors are guaranteed to lose

money on the bonds if they hold them to maturity.

And, these bonds have been the fastest growing asset class in

Europe with the total amount of euro government debt and bills yielding

below zero has surged to 1.2 trillion euros from 500 billion in October

and zero in June!

-

Here is the mentality of an institutional bond

trader in Europe – “You've got over 1 trillion of euros that will be

created. All of that new money

needs to find a home," said Thomas Urano, a managing director at

fixed-income manager Sage Advisory. "I could park it in the bank and

lose money for certain or I could put it into a corporate bond and maybe

only lose one basis point."

Amazing!

Even though global

central banks have printed over $11 trillion dollars in the past 5 years

we are sliding, in a number of areas around the world, to where savers

have to pay banks to hold their money and in some cases, the bank pays

the borrower to take out a loan.

PUTTING THINGS INTO

PERSPECTIVE…

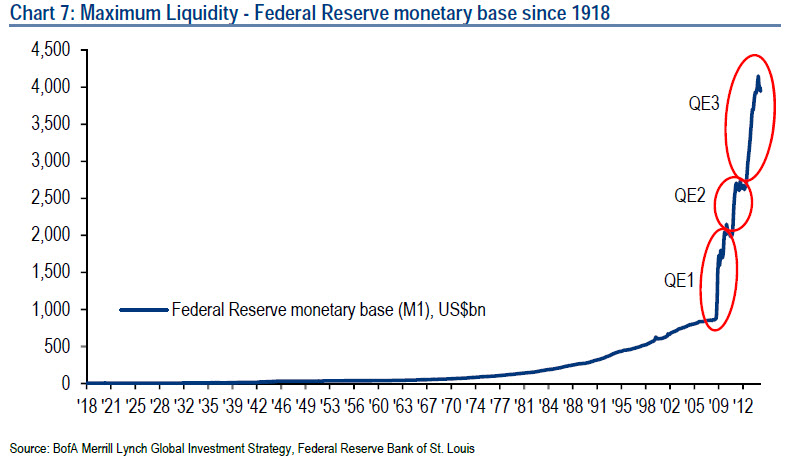

To highlight the

backdrop of this emerging world of bizarre finance, we can look at the

following three charts.

The chart above shows

our Central Bank’s monetary base.

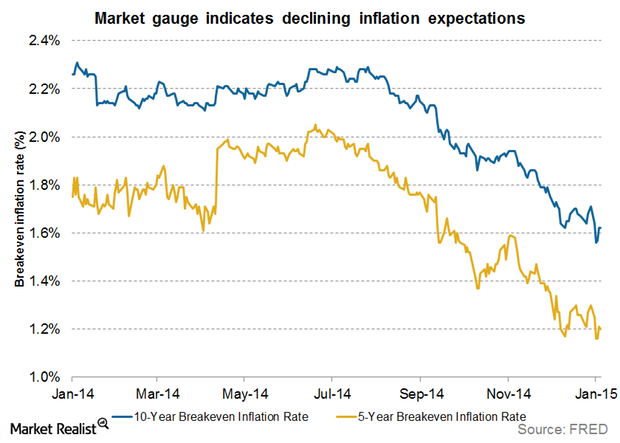

The chart above shows

market based inflation expectations even with all the free money.

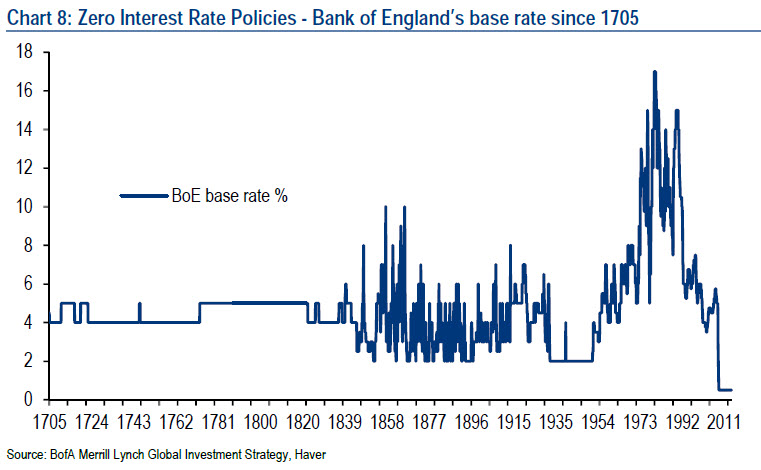

Now, let’s put this

into further historical context with the following chart.

The chart above shows

the interest rate policy set by the Bank of England going back to 1705,

covering over 300 years. As

the chart illustrates, they have never been as low as they are

now...how’s that for perspective!

WHAT IF RATES GO NEGATIVE

HERE???

We are likely to see an

increasing number of oddities in the financial world as the global

economic and central bank environment evolves.

It would be interesting to see what kinds of behavior would occur

if rates were to go negative here in the U.S. like they are in parts of

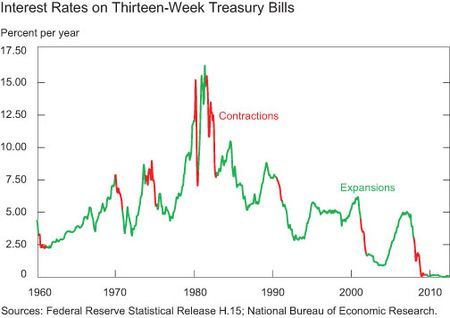

Europe now. Here is a

long-term chart of short-term Treasury-bill yields from an article by

Kenneth Garbade and Jamie McAndrews of the NY Fed back in August of

2012.

Rates are at the floor

so the next step is into negative territory if the deflation in Europe

and Japan continues to come onto our shores.

As an additional read, I have posted the article at the end of

this commentary by those two at the NY Fed contemplating the strange and

possible behaviors that they believe may occur in a negative rate

environment.

While the volatility

has increased in the stock market over the past two months, there seems

to be little concern among investors.

In fact, the latest Bloomberg poll finds investors to be the most

bullish they have been in five years.

However, it would be unusual to see the type of volatile

movements in the currency, commodity and interest rate markets like we

have seen over the past number of months without it spilling over into

the broader equity markets.

We continue to live in historical times relating to the financial

markets and I think the types of oddities that are beginning to surface,

which I highlighted above, are just getting started.

Take a look at the commentary below from the two at the NY Fed to

get your imagination going.

Some of it may seem far-fetched but a number of countries are already

going to negative rates and that seemed far-fetched not too long ago.

Joseph R. Gregory, Jr.

If Interest Rates Go

Negative . . . Or, Be Careful What You Wish For

By Kenneth Garbade and

Jamie McAndrews. August,

2012.

The United States has

slid into eight recessions in the last fifty years.

Each time, the Federal Reserve sought to revive economic activity

by reducing interest rates.

However, since the end of the last recession in June 2009, the economy

has continued to sputter even though short-term rates have remained near

zero. The weak recovery has

led some commentators to suggest that the Fed should push short-term

rates even lower—below zero—so that borrowers receive, and creditors

pay, interest.

One way to push

short-term rates negative would be to charge interest on excess bank

reserves. The interest rate

paid by the Fed on excess reserves, the so-called IOER, is a benchmark

for a wide variety of short-term rates, including rates on Treasury

bills, commercial paper, and interbank loans.

If the Fed pushes the IOER below zero, other rates are likely to

follow.

Without taking a

position on either the merits of negative interest rates or the Fed's

statutory authority to fix the IOER below zero, this post examines some

of the possible consequences. We

suggest that significantly negative rates—that is, rates below -50 basis

points—may spawn a variety of financial innovations, such as

special-purpose banks and the use of certified bank checks in

large-value transactions, and novel preferences, such as a preference

for making early and/or excess payments to creditworthy counterparties

and a preference for receiving payments in forms that facilitate

deferred collection. Such

responses should be expected in a market-based economy but may

nevertheless present new problems for financial service providers (when

their products and services are used in ways not previously anticipated)

and for regulators (if novel private sector behavior leads to new types

of systemic risk).

Cash and Cash-like

Products:

The usual rejoinder to

a proposal for negative interest rates is that negative rates are

impossible; market participants will simply choose to hold cash.

But cash is not a realistic

alternative for corporations and state and local governments, or for

wealthy individuals. The largest

denomination bill available today is the $100 bill.

It would take ten thousand such

bills to make $1 million. Ten

thousand bills take up a lot of space, are costly to transport, and

present significant security problems. Nevertheless,

if rates go negative, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Bureau of Engraving

and Printing will likely be called upon to print a lot more currency as

individuals and small businesses substitute cash for at least some of

their bank balances.

If rates go negative,

we should also expect to see financial innovations that emulate cash in

more convenient forms. One

obvious candidate is a special-purpose bank that offers conventional

checking accounts (for a fee) and pledges to hold no asset other than

cash (which it immobilizes in a very large vault).

Checks written on accounts in a

special-purpose bank would be tantamount to negotiable warehouse

receipts on the bank’s cash. Special-purpose

banks would probably not be viable for small accounts or if interest

rates are only slightly below zero, say -25 or -50 basis points (because

break-even account fees are likely to be larger), but might start to

become attractive if rates go much lower.

Early Payments, Excess

Payments, and Deferred Collections:

Beyond cash and

special-purpose banks, a variety of interest-avoidance strategies might

emerge in connection with payments and collections.

For example, a taxpayer might

choose to make large excess payments on her quarterly estimated federal

income tax filings, with the idea of recovering the excess payments the

following April. Similarly, a

credit card holder might choose to make a large advance payment and then

run down his balance with subsequent expenditures, reversing the usual

practice of making purchases first and payments later.

We might also see some

relatively simple avoidance strategies in connection with conventional

payments. If I receive a check

from the federal government, or some other creditworthy enterprise, I

might choose to put the check in a drawer for a few months rather than

deposit it in a bank (which charges interest).

In fact, I might even go to my

bank and withdraw funds in the form of a certified check made payable to

myself, and then put that check in a drawer.

Certified checks, which

are liabilities of the certifying banks rather than individual

depositors, might become a popular means of payment, as well as an

attractive store of value, because they can be made payable to order and

can be endorsed to subsequent payees. Commercial

banks might find their liabilities shifting from deposits (on which they

charge interest) to certified checks outstanding (where assessing

interest charges could be more challenging).

If bank liabilities shifted from

deposits to certified checks to a significant degree, banks might be

less willing to extend loans, because certified checks are likely to be

less stable than deposits as a source of funding.

As interest rates go

more negative, market participants will have increasing incentives to

make payments quickly and to receive payments in forms that can be

collected slowly. This is

exactly the opposite of what happened when short-term interest rates

skyrocketed in the late 1970s: people then wanted to delay making

payments as long as possible and to collect payments as quickly as

possible. Some corporations

chose to write checks on remote banks (to delay collection as long as

possible), and consumers learned to cash checks quickly, even if that

meant more trips to the bank, and to demand direct deposits.

However, if interest rates go

negative, the incentives reverse: people receiving payments will prefer

checks (which can be held back from collection) to electronic transfers.

Such a reversal could impose

novel burdens on payment systems that have evolved in an environment of

positive interest rates.

Conclusion:

The take-away from this

post is that if interest rates go negative, we may see an epochal

outburst of socially unproductive—even if individually

beneficial—financial innovation. Financial

service providers are likely to find their products and services being

used in volumes and ways not previously anticipated, and regulators may

find that private sector responses to negative interest rates have

spawned new risks that are not fully priced by market participants.